Abdominal work can be bad for your back

Core strengthening has become a buzzword in the fitness world - there's a great emphasis on core strengthening and particularly abdominal strenghtening in most fitness programs. As yoga therapists our main interest in core strengthening is the support of the pelvis and the spine. In numerous studies and in our own therapy practice, working with people with back problems we've observed that the strengthening of the muscles that are supposed to be supporting the spine and pelvis is a critical component for relieving pain and restoring healthy movement. A number of clients with chronic and severe back pain were greatly improved or even eliminated pain by strengthening the support system.

When people think of core strengthening, most think of crunches and sit-ups. However, a focus solely on abdominal work and abdominal strengthening can actually be counterproductive on a number of important levels.

A lot of people don't understand that if you're going to strengthen the front you also need to strengthen the back! The folks who spend all or a majority of their core strengthening time working the front of the body find the abdominals get shorter and shorter, (including the chest muscles) and as a result the muscles in the back become relatively weak and overstretched compared to the front body. This results in the person being pulled over by short abdominal action. When the abdominal muscles get overly short and tight they hold you in a flexed, slumped position. This leads to all kinds of problematic implications; everything from neck pain and headache because if you're slumped forward the head is forward and that puts a lot of extra pressure and stress on the neck and shoulders. And we've seen it can also lead to problems with the jaw and the mid-back. Tight abdominals and being overly rounded also puts pressure and limits the movement of the diaphragm, so that it has implications on your ability to breathe and notably the ability take a full breath.

To breathe normally and to take a full breath is obviously really important in yoga but it's also important for just about any other activity. On top of all that, an overly flexed position can also contribute to lower back problems as well.

It's not just the abdominals, the obliques also attach to the front lower ribs and when they are short they pull down on the front ribcage and that rounds the chest over and down. The implications in terms of yoga is that it's going to limit your ability to do any kind of back bends — the abdomen has to lengthen when were doing any kind of back bending.

We've seen in a number of cases that being very short in the front body takes the normal curve out of the lower back, flattening the normal lumbar curve. The person's movement patterns — that's everything they do, is organized around a flatback position and that puts pressure on the discs in such a way that it can set the stage for injury. One of the first things that you have to do is train them how to lengthen the front body to help restore the normal curve of the lower back and allow the back heel.

It is possible to restore the natural curve, even if you're chronically locked in a forward slumped position. You may have had a serious injury to the discs and sometimes the bones are fused but most of the time they're not, so if the bones are not fused you can restore so much of the normal alignment. But you have to work at it — you have to change your movement habits to change your muscle balance. We've seen a number of clients with serious injury be able to be completely pain-free but it doesn't happen over night, you have to be persistent and work at it regularly. That's the good news and the message we often find ourselves saying.

Especially noticeable in yoga, when the abs are tight and short they can effect your ability to do any kind of backbend because the mid-back is stuck in flexion. So for example if you're trying to do bridge pose you can't get your back lifted-very much off the floor. If you're laying on your stomach and you go to lift up in cobra pose for example, you won't be able to come up very high off the floor because the front body is short and holds the chest relatively close to the pelvis, so you can't go into very much extension.

When teaching a group or workshop you can more easily observe how the spine moves, and if you're doing something simple like cat/camel, we often see that people who are rounded-over have very little extension, and extension is supposed to be the normal movement of the spine.

The good news is that you can definitely change over time but there's a lot of layers of muscles in the abdomen, the chest, the pectorals and the intercostal muscles between the rib — if they're all short in the front it takes time to re-lengthen all these muscle groups and fibers… it doesn't happen overnight. And when we say "muscles" we're not only talking about the contractile muscles but also the fascia. The makeup of the muscle includes thick, heavy bands of fascia, especially in the abdomen and in the back as well and all of that can become short, so it's not just the contractile muscle tissue.

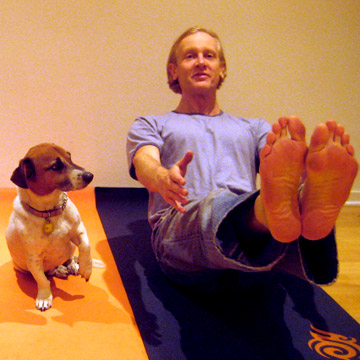

There's such a wonderful variety of strengthening that we do with yoga poses. We were talking to physical therapists the other day about how in yoga we do the strengthening by supporting the weight of our body parts in various orientations to gravity. Sometimes we're standing, sometimes we're upside down, sometimes we're sideways, sometimes we're face up or down on the floor. Then the lifting of the body part whether it's the arm, leg or torso is going to strengthen the huge variety of muscle groups according to how gravity is pulling on the body part — that's how a lot of abdominal strengthening happens and people aren't even aware of it.

Standing poses are one example like Triangle, Extended Side Angle and Half Moon where your torso muscles, including the obliques and transversus abdominis are contracting to hold up the weight of your torso which is parallel to the floor. In Triangle pose the side abdomen flank muscles are contracting to hold the weight of your torso. If you're also rotating your torso, (which we are doing in those sideways poses) some of the abdominal muscles are rotators, so they rotate the torso — they get kind of a double whammy, the obliques in particular holding up the weight of the body as you go sideways and rotating the torso at the same time. So it's fabulous, functional oblique strengthening. One of the things that we love about strengthening in yoga in general, is that we're training functional muscle patterns.

Lots of times when you go to the weight room you're isolating a particular muscle, say the biceps for example, you're sitting at a machine and everything is supported, so you're really isolating just the biceps or just the triceps — that's fine especially if you have a lack of strength in that muscle and you're trying to build it back up to normal strength. However, in yoga we're actually training muscles to work together in functional patterns which is really valuable for everyday life on the planet. Let's say you have an extremely strong isolated bicep for example, if you want to go lift something heavy, you think I've got a nice strong bicep here for lifting, however, you haven't strengthened the other muscles that you need to stabilize the scapula and stabilize the spine, so you have a strong bicep but the rest of the muscle pattern that you need to actually do a functional activity isn't there. We've actually seen a fair number of injuries in weightlifters because they had isolated certain muscles and gotten really strong but not the rest of the team.

Muscle imbalances can pre-dispose you to injury — muscle imbalances you create through differential training. You may also have pre-existing asymmetries in your body and when you add extra weight you exacerbate any chronic conditions. In yoga we stretch the tight areas and strengthen the weak areas, this comes naturally in any balance yoga posture for example. However, our human ego says we'd rather do the stuff thats much more fun — the stuff you're competent and good at. It's not so much fun to do the stuff that's hard, so unfortunately, many people gravitate away from strengthening the weak areas and stretching the tight areas.

By John & Mary Jo Johnson, (C-IAYT)